Originally published in Lake of the Woods Area News, Volume 55, Number 5, Winter 2025

Exploring the remarkable adaptations and timeless appeal of these endearing backyard birds

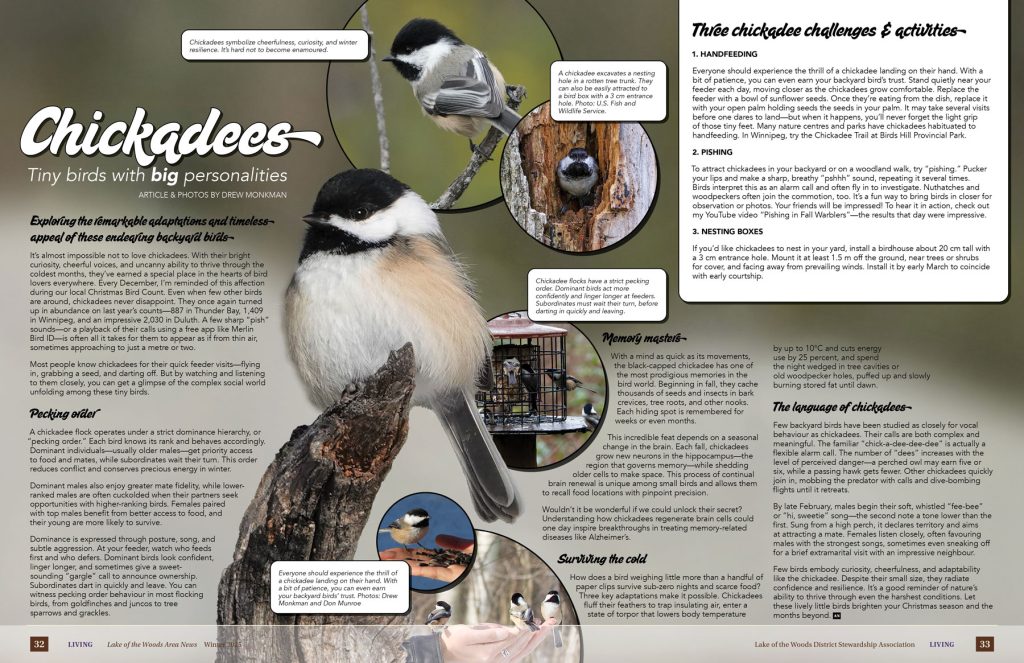

It’s almost impossible not to love chickadees. With their bright curiosity, cheerful voices, and uncanny ability to thrive through the coldest months, they’ve earned a special place in the hearts of bird lovers everywhere. Every December, I’m reminded of this affection during our local Christmas Bird Count. Even when few other birds are around, chickadees never disappoint. They once again turned up in abundance on last year’s counts—887 in Thunder Bay, 1,409 in Winnipeg, and an impressive 2,030 in Duluth. A few sharp “pish” sounds—or a playback of their calls using a free app like Merlin Bird ID—is often all it takes for them to appear as if from thin air, sometimes approaching to just a metre or two.

Most people know chickadees for their quick feeder visits—flying in, grabbing a seed, and darting off. But by watching and listening to them closely, you can get a glimpse of the complex social world unfolding among these tiny birds.

Pecking order

A chickadee flock operates under a strict dominance hierarchy, or “pecking order.” Each bird knows its rank and behaves accordingly. Dominant individuals—usually older males—get priority access to food and mates, while subordinates wait their turn. This order reduces conflict and conserves precious energy in winter.

Dominant males also enjoy greater mate fidelity, while lower-ranked males are often cuckolded when their partners seek opportunities with higher-ranking birds. Females paired with top males benefit from better access to food, and their young are more likely to survive.

Dominance is expressed through posture, song, and subtle aggression. At your feeder, watch who feeds first and who defers. Dominant birds look confident, linger longer, and sometimes give a sweet-sounding “gargle” call to announce ownership. Subordinates dart in quickly and leave. You can witness pecking order behaviour in most flocking birds, from goldfinches and juncos to tree

sparrows and grackles.

Memory masters

With a mind as quick as its movements, the black-capped chickadee has one of the most prodigious memories in the bird world. Beginning in fall, they cache thousands of seeds and insects in bark crevices, tree roots, and other nooks. Each hiding spot is remembered for weeks or even months.

This incredible feat depends on a seasonal change in the brain. Each fall, chickadees grow new neurons in the hippocampus—the region that governs memory—while shedding older cells to make space. This process of continual brain renewal is unique among small birds and allows them to recall food locations with pinpoint precision.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could unlock their secret? Understanding how chickadees regenerate brain cells could one day inspire breakthroughs in treating memory-related diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Surviving the cold

How does a bird weighing little more than a handful of paper clips survive sub-zero nights and scarce food? Three key adaptations make it possible. Chickadees fluff their feathers to trap insulating air, enter a state of torpor that lowers body temperature by up to 10°C and cuts energy use by 25 percent, and spend the night wedged in tree cavities or old woodpecker holes, puffed up and slowly burning stored fat until dawn.

The language of chickadees

Few backyard birds have been studied as closely for vocal behaviour as chickadees. Their calls are both complex and meaningful. The familiar “chick-a-dee-dee-dee” is actually a flexible alarm call. The number of “dees” increases with the level of perceived danger—a perched owl may earn five or six, while a passing hawk gets fewer. Other chickadees quickly join in, mobbing the predator with calls and dive-bombing flights until it retreats.

By late February, males begin their soft, whistled “fee-bee” or “hi, sweetie” song—the second note a tone lower than the first. Sung from a high perch, it declares territory and aims at attracting a mate. Females listen closely, often favouring males with the strongest songs, sometimes even sneaking off for a brief extramarital visit with an impressive neighbour.

Few birds embody curiosity, cheerfulness, and adaptability like the chickadee. Despite their small size, they radiate confidence and resilience. It’s a good reminder of nature’s ability to thrive through even the harshest conditions. Let these lively little birds brighten your Christmas season and the months beyond.

Three chickadee challenges & activities

1. Handfeeding

Everyone should experience the thrill of a chickadee landing on their hand. With a bit of patience, you can even earn your backyard bird’s trust. Stand quietly near your feeder each day, moving closer as the chickadees grow comfortable. Replace the feeder with a bowl of sunflower seeds. Once they’re eating from the dish, replace it with your open palm holding seeds the seeds in your palm. It may take several visits before one dares to land—but when it happens, you’ll never forget the light grip of those tiny feet. Many nature centres and parks have chickadees habituated to handfeeding. In Winnipeg, try the Chickadee Trail at Birds Hill Provincial Park.

2. Pishing

To attract chickadees in your backyard or on a woodland walk, try “pishing.” Pucker your lips and make a sharp, breathy “pshhh” sound, repeating it several times. Birds interpret this as an alarm call and often fly in to investigate. Nuthatches and woodpeckers often join the commotion, too. It’s a fun way to bring birds in closer for observation or photos. Your friends will be impressed! To hear it in action, check out my YouTube video “Pishing in Fall Warblers”—the results that day were impressive.

3. Nesting boxes

If you’d like chickadees to nest in your yard, install a birdhouse about 20 cm tall with a 3 cm entrance hole. Mount it at least 1.5 m off the ground, near trees or shrubs for cover, and facing away from prevailing winds. Install it by early March to coincide with early courtship.