Originally published in Lake of the Woods Area News, Volume 55, Number 4, Fall 2025

In case you hadn’t noticed, IISD Experimental Lakes Area—the world’s freshwater laboratory—is located in this very remote part of northwestern Ontario.

The intense winters and glorious summers mean that we must work within the changing cycles of weather and a changing climate. Predicting the weather is tough but knowing when the lakes are going to freeze and thaw helps us plan for the summer seasons.

This is where artificial intelligence (AI) and its capacity for predictive modelling can flex its muscles—harvesting and analyzing our rich dataset on the history of our lakes to accurately predict when we can expect “ice-off.”

How can we predict when our lakes will thaw in the spring?

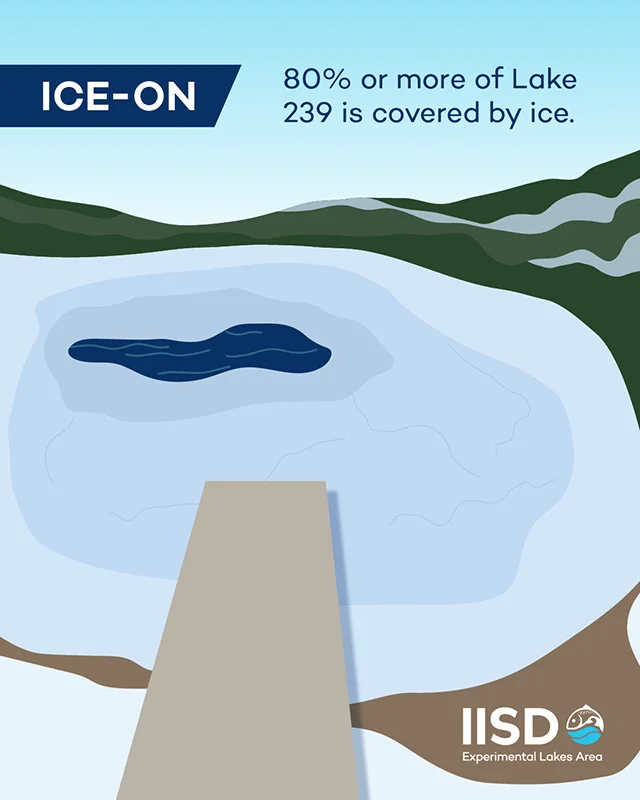

First, some definitions. Using Lake 239 as our reference point:

- Ice-on occurs as winter sets in and is defined as the day when Lake 239 has achieved 80 per cent (or more) ice coverage.

- Ice-off occurs as spring settles in and is defined as the date when no significant ice remains on the lake, since ice goes from nearly complete coverage to no coverage in the span of a single day.

Using the historical data that we already have for Lake 239, we trained a random forest model on decades of related data, as well as the historical ice-off dates from 1969.

This model is definitely in its pilot stage, but we have already determined that it can predict the ice-off date up to a month in advance and has proven to be accurate to within about 1.7 days, on average. In fact, in 2025 it was only a day off, predicting May 3, 2025, when ice-off was officially declared on May 4, 2025.

This means we can prepare for boots on the ground ahead of time, making planning for research, materials, and logistics so much more efficient and cost effective.

Next step? We want to see if we could train the model to make similar predictions for other lakes at the site, and even further afield from IISD-ELA in the boreal forest.

Where else are we using artificial intelligence at the world’s freshwater laboratory?

AI for quality control

Throughout each field season, data is collected daily from sites across IISD-ELA, on land, on boats, and beneath the water’s surface. However, humans can make mistakes and so can machines.

That’s why we are looking into the potential for AI to identify patterns in our data, from mislabelled samples to damaged or malfunctioning sensors. By identifying these patterns, AI can help our scientists and field technicians identify issues early, allowing them to spend more time in the field and less time at their desks.

AI for water management

Beyond the world’s freshwater laboratory, freshwater ecosystems can span hundreds of kilometres, providing life-supporting benefits to human and non-human communities.

We are, therefore, exploring how AI could provide decision-makers with data on river flows, wetlands, and nutrients in Manitoba watersheds to help them make better-informed and more effective water management and conservation decisions.

How else could these artificial intelligence solutions be used to understand Canada’s environment better?

These very principles and tools could be applied to predict other annual environmental events beyond IISD-ELA.

A few potential applications include:

- Predicting when ice roads will start to melt would be an invaluable use of this model, especially set against the backdrop of climate change and the uncertainty that brings. If the historical data are there, they could be fed into a similar model used for ice-off on Lake 239 to make accurate predictions about when the ice roads will prove to be untenable and unsafe to use.

- Similar forecasting models could also be used to estimate the impacts of future climate scenarios on our freshwater ecosystems. For example, what will the scale and composition of algal blooms be under a given set of circumstances, what would this mean for freshwater health, and how can we then efficiently mitigate the impact?

- In time, AI might also allow us to find intricate patterns that would be virtually impossible for humans to discover across big datasets, such as IISD-ELA’s six-decade historical database of the health of our lakes or using existing data from lakes and rivers across the globe.